The source code for this project is here. This is the second in a series of posts where I unpack how I do something computational piece by piece; check out the first post here.

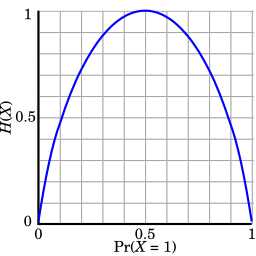

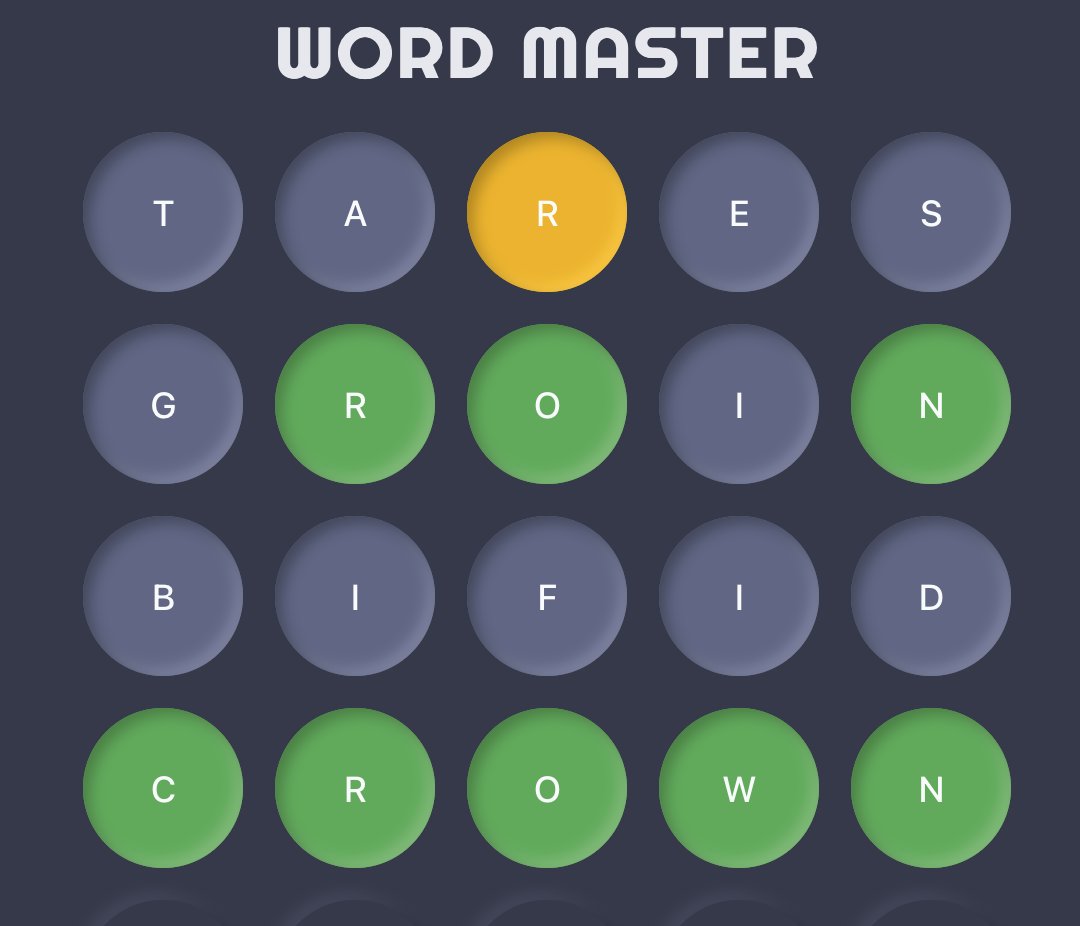

Having recently posted about my Sudoku solver, let’s start ruining the human aspect of another popular game! This time we’re talking about Wordle, the game that’s taken the internet by storm for the past ten days. You have six attempts to guess a five-letter word. In each guess, for each letter, you’re told whether the letter doesn’t show up in the word (it comes up grey), whether it shows up but not where you said it did (yellow), or if you got the letter and the position both right (green). Here’s one I did last week.

In this case, the solution space is known, and what’s limited is our ability to explore it, so this is a game of being maximally efficient with the little space we have. You can tell in the above example that I wasn’t perfectly efficient: I guessed “miles” after “vibes” even though I knew the “e” and “s” weren’t there, and I guessed “sidle” after finding out there wasn’t an “L” anywhere. I took six guesses to get this one, but I could’ve done it in fewer. How do I know this for sure? To answer that, we’ll take a quick dive into information theory, and the central concept of entropy.

Information theory is a branch of electrical engineering/computer science that deals with efficient ways to handle information: how to figure out how much information is in a certain amount of data, how to send or receive information efficiently and without being vulnerable to errors, and how to place fundamental limits on the sorts of problems we’re dealing with here. For this solver, I’ll use the most essential tool in information theory: entropy.

Entropy

Entropy is a concept that expresses how much uncertainty there is in something we don’t perfectly know. A simpler example of when we use this is in a number guessing game. Suppose I think of a number between 1 and 100, and ask you to guess it: after each of your guesses, I’ll tell you if you guessed too high, too low, or exactly right. Your job is to take the minimum number of guesses you can and get the number right.

Let’s play now!

36? Too low.

83? Too high.

42? Too low.

79? Too high.

56? Too low.

66? Too low.

73? Too low.

76? Too high.

75? That’s it!

You can see this wasn’t very efficient - we spent a lot of time dancing around the actual number, and we only really got a good sense of what it was near the end. For most of the middle, the range of numbers it could’ve been was really high, and you might get the idea that with a smarter guessing strategy, you could’ve made that range smaller in a lot less time.

After a bit of experimenting, you’ll probably hit on the optimal strategy, which is to halve the search space every time. You start by guessing 50, right in the middle, and either you just got it right, or you now have a range of 50(ish) numbers to guess from - either you’re guessing 1-49 because I said you went too high, or 51-100 because I said you went too low. Then you do it again, and you’ve got 25 numbers to choose from. Again, it’s 12-13, again, it’s about 6, then 3, 2, 1. Within about six or seven guesses, you’ll get it, just by halving the space every time.

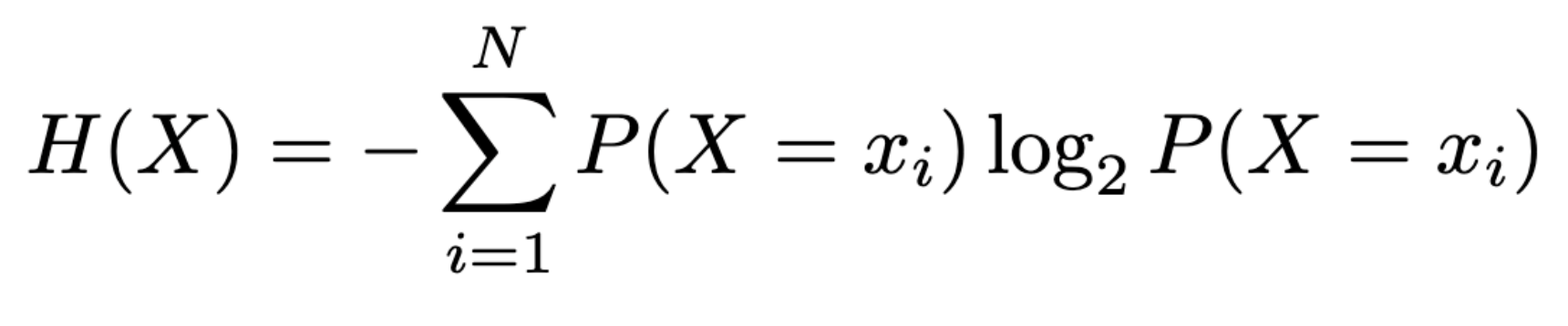

I initially started to prove that this was really optimizing the known binary entropy function, but that quickly got too technical for a post about a fun word game, so I’ll make that into its own post later. For now, I’ll just say that people have analyzed this and similar problems of narrowing down an unknown from information, and have come up with this metric for “surprise”: if there’s some random variable X with N possible values (x1, x2, …, xN) whose probabilities we know, the entropy of X is

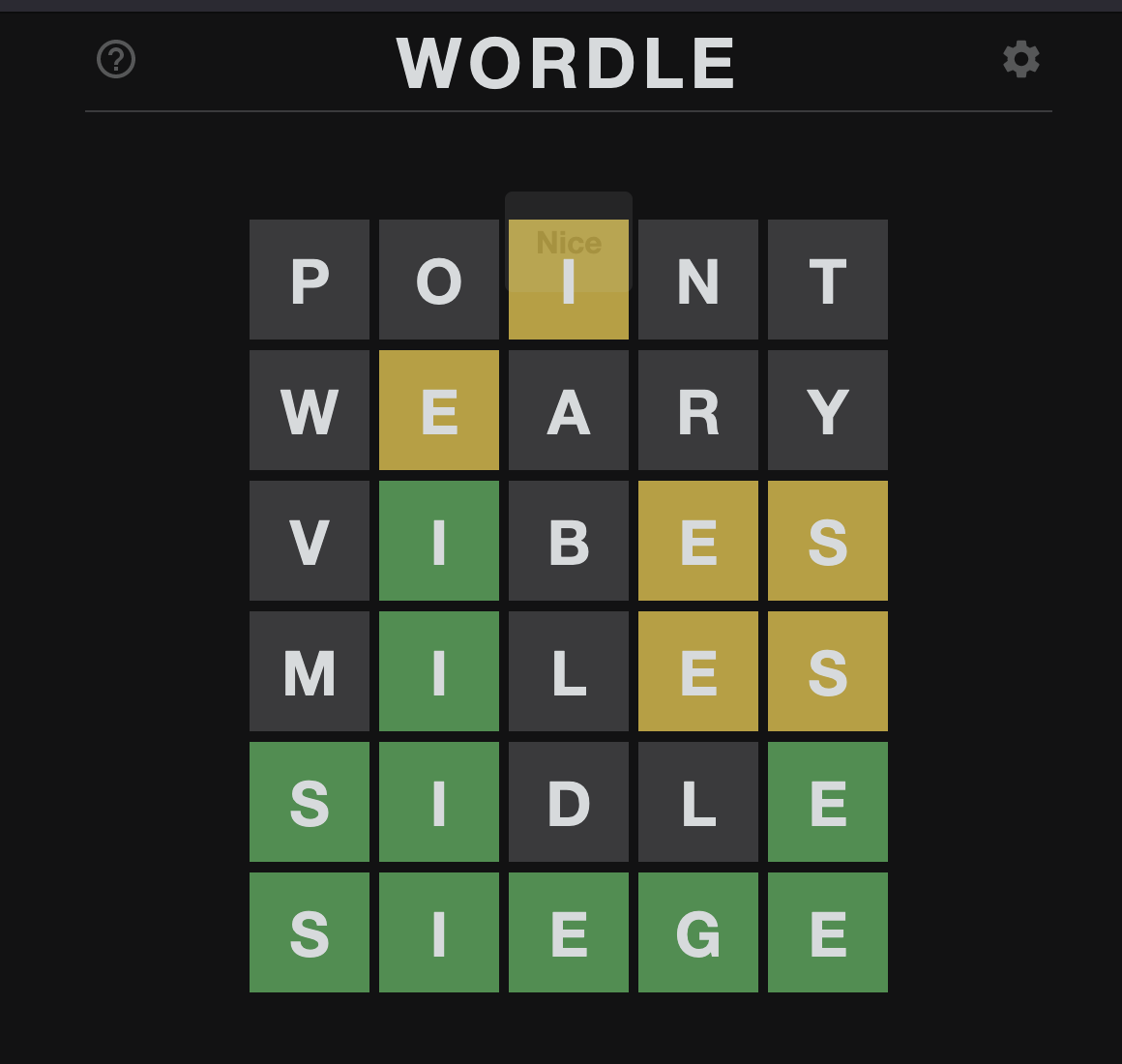

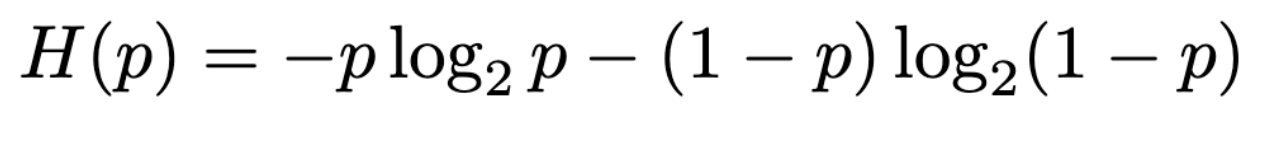

When N = 2, the only possibilities are x_1 and x_2; if we let the probability of getting one of these be p and the other be 1-p, we get the binary entropy function:

Here’s what that looks like! (This image is from the Wikipedia page on the binary entropy function.)

This answers the question: “if I flip a coin with probability p of coming up heads, how surprised am I to see the result?” Here, we’re normalizing one “unit of surprise” (sometimes “one shannon”, after the inventor of the field, Claude Shannon) to be how surprised we are at the outcome of a fair coin flip.

- If p = 0 or p = 1, there’s no surprise at all, because we know it’ll always come up heads or tails.

- If p is anything in between except for 0.5, we know it’s biased to one side or another, so we’re less surprised accordingly. For example, if p = 0.1, we have an expectation that it’ll probably be tails, so most of the time observing the outcome doesn’t tell us much that we couldn’t have already guessed.

- If p = 0.5, we don’t really have anything to go on, so no matter what happens, we’re the most “surprised” we can be.

We won’t have to work with the exact entropy function that much, but one thing that’s noteworthy is that the distribution that maximises entropy for a fixed N is the uniform distribution: P(X = x1) = 1/N, P(X = x2) = 1/N, and so on up to P(X = xN) = 1/N. This can start telling us what the best Wordle solver looks like: instead of fixing the greatest number of green letters, you want to pick the word that’s most likely to equally partition the search space.

The best algorithm for Wordle

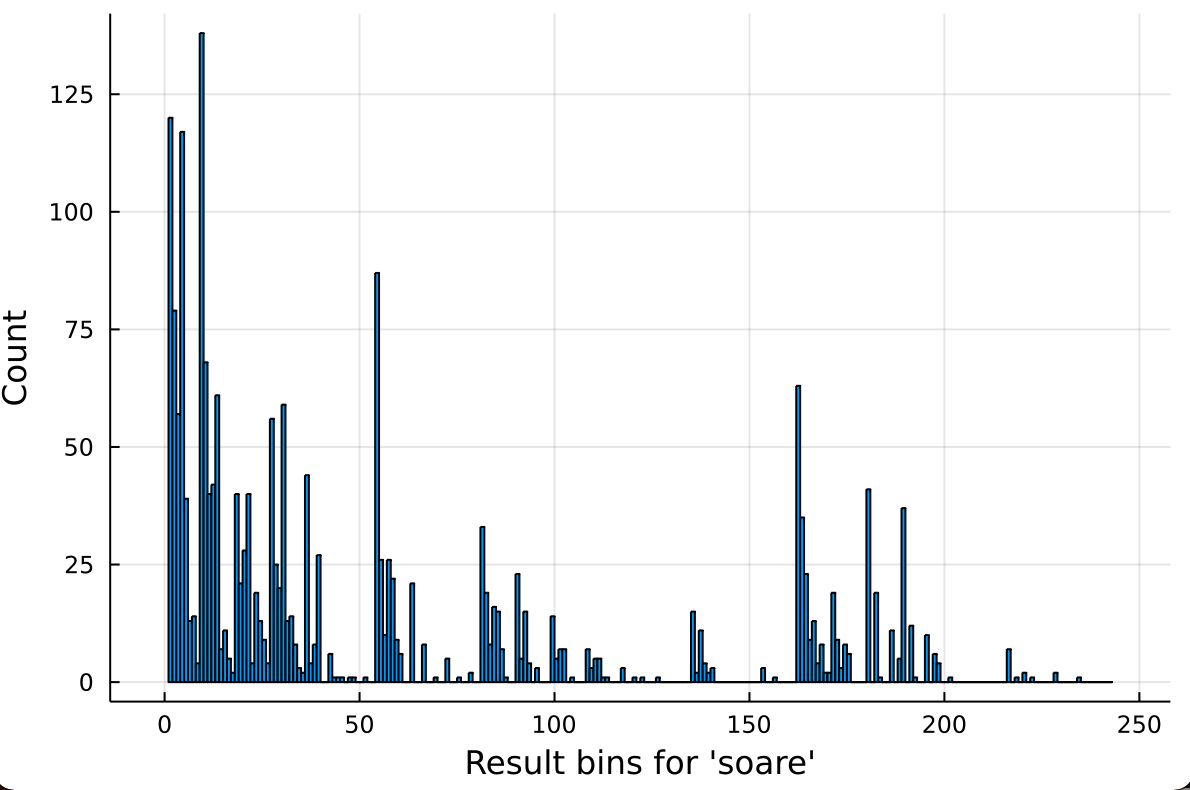

Let’s start thinking about how this framework could be applied to Wordle. When you make a guess, there’s 243 possible results: the three outcomes of (grey, yellow, green) to the power 5 because it’s possible independently for each letter. Of the 2315 possible answers in Wordle, a fixed guess will result in one of these 243 results, so our first guess will partition the search space and pick one of those 243 buckets. If we happen to get the “all green” bucket, we’re immediately done, but we’ll almost certainly land up in one of the other buckets. Here’s the sizes of different buckets for ‘soare’, which will turn out to be our choice for the first guess:

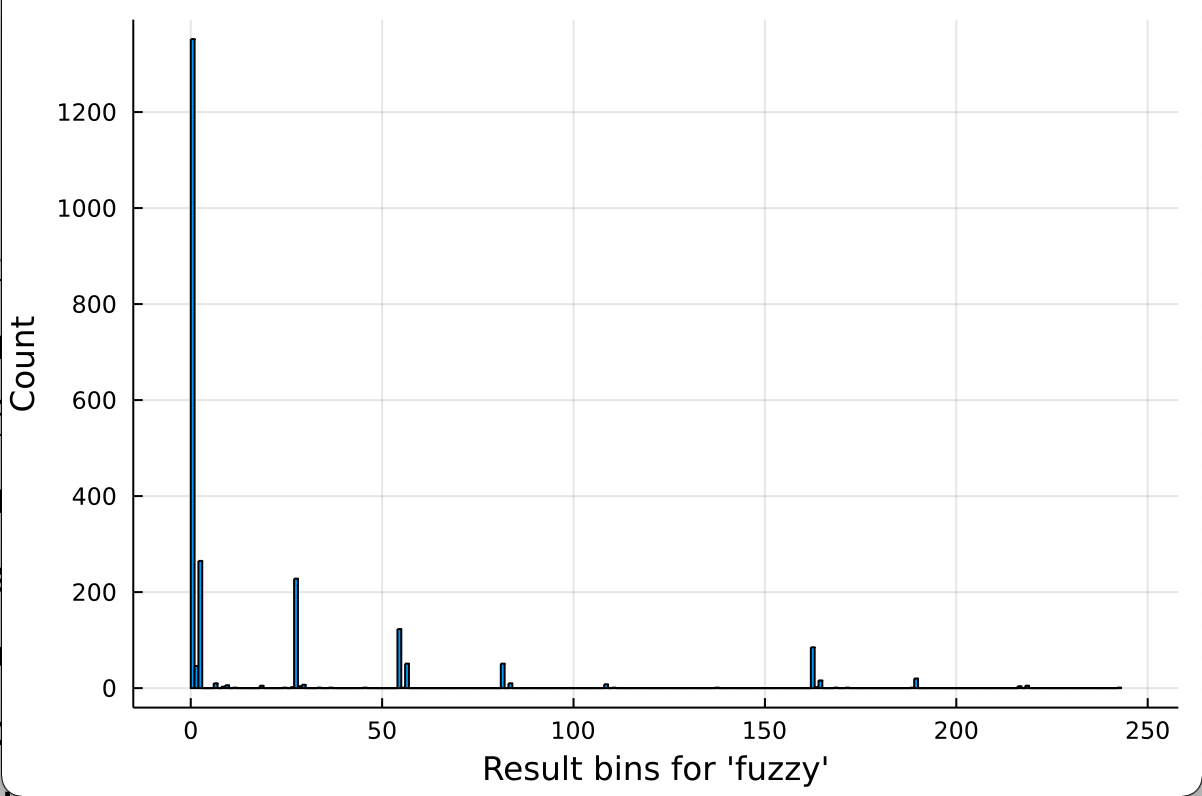

And here’s the same distribution if our first guess is ‘fuzzy’, one of the worst:

The biggest bin in the second case (and the second biggest in the first) is the leftmost one, which maps to everything being grey. In most cases, there’s more words that don’t have any of those letters than those that have any particular combination of them.

We’re presented with the following tradeoff: the more likely you are to land in a particular bin, the more difficult it is to guess your way down from there, because you landed in one that was likely. Suppose you guessed “fuzzy” to start with. There’s an outside chance that you get (grey, grey, green, green, grey) from “fuzzy”, and that tells you it has to be “pizza” because that’s the only other word with a double ‘z’. However, this isn’t what you’ll see most of the time: in more than half the games of Wordle, you’ll just get all-greys from this, and you’re more or less back to the drawing board. By contrast, most of the time “soare” will leave you with something to go on – even if it’s all grey, you’ll know you can knock out any word that has five of the most common letters, which turns out to leave you with just 183 words, down from 2315! 183 is a lot more than the 1 that our “fuzzy” -> “pizza” example gave us, but because there’s 183 of them, it’s also 183 times more likely we get there.

This is exactly the same quandary we had in the guessing game. There, if you picked, say, 90 right off the bat, most of the time you’d have a huge search space left over, but sometimes you’d restrict yourself to just the numbers 91-100 and make your job much easier. How do you find the sweet spot where you’re almost always going to be left with a small search space?

This is the benefit of seeking out distributions that are as close as possible to uniform. In expectation, it’s a lot better to get a guaranteed reduction to 1/N than it would be to gamble and sometimes get an instant solution but more often get no useful information. This intuition is backed up by our discussion of entropy earlier. You want results that have the most “surprise” in them, so that they’re ideally only telling you things you don’t already know.

Summing up, what we’d like a solver to do is to check every possible guess against a corpus of candidate answers, figure out the split into these 243 buckets, and pick the guess that most evenly distributes that split as measured by the entropy function.

Implementing the solution

Wordle has two lists of words: about ten thousand valid guesses, and the aforementioned 2315 possible solutions. I also used the Word Master clone of Wordle to get around the one-a-day limit, which has slightly different lists. This doesn’t change the approach, but it might change which word turns out to be optimal. To include both compactly, I made a struct named possibles that contains the list of possible guesses, possibles.words, and the list of possible answers, possibles.answers. If you notice possibles anywhere in the code without a definition, that’s what it means.

The solver needs to do two things repeatedly:

- Pick the word with the best-entropy splitting in the corpus (then on the real game, guess that word, and see the result)

- Filter the corpus to only include words that fit the result we just got.

We’ll do this until the corpus has only one word left, or until we’ve gone over the number of guesses.

Because it’s easier, let’s start with the second one, which I put into a function called constrain. (If you’d just like to see how the entropy part works, skip ahead to where I wrote the word “dinosaur” in a header.) Initially I had constrain be a self-contained function, but then I wanted to simulate actual games in my terminal and I needed to split the word-matching logic, so we’ve got the following wonderfully easy start:

This needs us to implement the function guess(query, answer), which returns the (grey, yellow, green) match between the query and the answer. I’m using the mapping 0 -> grey, 1 -> yellow, 2 -> green because it’s the easiest representation to type and remember (although Julia has full Unicode support, so replacing this in the terminal with actual boxes with those colours would be possible!), so this will return a length-5 string with only those digits in it.

My initial logic for this was almost correct:

- Loop through the query

- If query[i] is answer[i], put down a green

- Otherwise, if query[i] is in the answer, put down a yellow

- Otherwise, leave it grey

However, a significant edge case in this left me with a program that was ruling out words it shouldn’t have been, and not finding solutions at all!

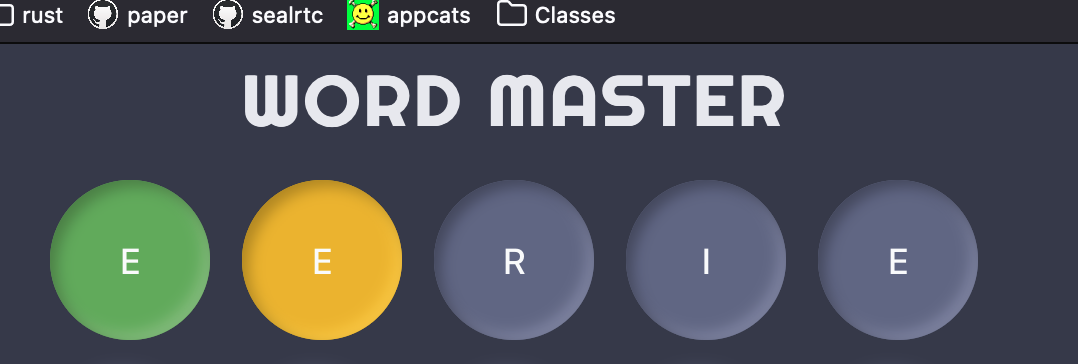

The issue turned out to be double letters. When you’re checking for yellows, Wordle will return as many matches as there are times that letter showed up, but no more, but I didn’t check how many times the letter showed up. For example, suppose the word is “elegy”, and I guessed “eerie”. Wordle/Wordmaster correctly only flags two ‘e’s:

However, the logic I outlined above returns “21001”, flagging the last ‘e’ as yellow as well and ruling out the actual answer! There’s no words in the answer set that match the result I was getting for that query.

To fix this, we just have to count how many times we’ve already seen a letter. I’m doing this with the countmap function in Julia, which goes through any iterable, counts up the number of times we see each item, and returns it in a dictionary. For example, with the word “elegy”, it’ll return (‘e’: 2, ‘l’: 1, ‘g: 1, ‘y’: 1). (In Python, collections.Counter does something similar.) Then, when we’re sorting through, we decrement that counter every time we see a letter that’s in there. Once we reach 0, we don’t flag anything as yellow.

For this to work, we need to flag all the greens first, so that we don’t accidentally put down grey instead of green as a result of having already seen enough of a certain letter. Putting all that together, here’s what we’ve got:

DINOSAUR

Now for choosing the best-split word! The naive way to do this would be:

- Loop through all 10k possible guesses

- Loop through all 2k possible answers

- Compute the match between them, say “12010”

- Throw that into some giant data structure that says “if we guessed this word, there’s one more case where we would get 12010”

- Find the entropy of the distribution we get by counting up all of these matches

- If that entropy is greater than the greatest so far, pick this word as our new guess

- Loop through all 2k possible answers

This is possible, but it would take a while to do all of that custom matching: on my machine, it’s on the order of 15-20 minutes. This isn’t bad to do one time and smartly store for later use, and it’s not like there’s a time limit for Wordle, but it kind of feels against the spirit of the game to me to just do all that precomputation and look up a giant table. I’d like a smarter way to do this entropy-splitting operation. I also probably don’t care about exact accuracy, since success is measured in the discrete number of guesses. If the word maximising the true entropy and the one maximising my approximation both get the answer in 4, does it matter that I made the approximation?

To speed this up, I added a preprocessing step: before we consider any potential guesses, we iterate through the corpus and find how many of each letter are at a certain index. For example, by counting over all the possible words, we find that A shows up at the second position 304 times and at the third position 307 times, so conditioned on a yellow A somewhere else, we might conclude that a word is good for splitting if it’s got an A in the second or third place, so we can figure out if our word is in the 304 or the 307. Whichever it is, we’ve halved our search space!

Here’s the full frequency set:

julia> for i in 0:25

char = 'a' + i

println(char, " frequency: ", has_char_in_pos[char])

end

a frequency: [141, 304, 307, 163, 64]

b frequency: [173, 16, 57, 24, 11]

c frequency: [198, 40, 56, 152, 31]

d frequency: [111, 20, 75, 69, 118]

e frequency: [72, 242, 177, 318, 424]

f frequency: [136, 8, 25, 35, 26]

g frequency: [115, 12, 67, 76, 41]

h frequency: [69, 144, 9, 28, 139]

i frequency: [34, 202, 266, 158, 11]

j frequency: [20, 2, 3, 2, 0]

k frequency: [20, 10, 12, 55, 113]

l frequency: [88, 201, 112, 162, 156]

m frequency: [107, 38, 61, 68, 42]

n frequency: [37, 87, 139, 182, 130]

o frequency: [41, 279, 244, 132, 58]

p frequency: [142, 61, 58, 50, 56]

q frequency: [23, 5, 1, 0, 0]

r frequency: [105, 267, 163, 152, 212]

s frequency: [366, 16, 80, 171, 36]

t frequency: [149, 77, 111, 139, 253]

u frequency: [33, 186, 165, 82, 1]

v frequency: [43, 15, 49, 46, 0]

w frequency: [83, 44, 26, 25, 17]

x frequency: [0, 14, 12, 3, 8]

y frequency: [6, 23, 29, 3, 364]

z frequency: [3, 2, 11, 20, 4]

This will help us look up the probability of a green match from a guess without looping over the whole potential answer set. Further, if we sum over all indices that aren’t that index, we can get an idea of the probability of a yellow match. Finally, the number of grey matches is just #words - #yellow - #green.

The approximation we end up using here is that it isn’t useful to do a yellow check for the absence of a double letter. By just summing over how many times a letter shows up, we’re not conditioning on anything in the word around it. However, double letters are infrequent enough in five-letter words that this won’t affect the result much. For the cost of this fairly reasonable approximation, we get to eliminate an inner loop and do an entropy-maximisation check that takes a fraction of a second!

All that’s left is to actually compute the differential entropy. To do this, we take the distribution of [grey, yellow, green] for each individual letter, compute its entropy, and add up that number for each of the five characters.

Using a dictionary here probably isn’t as efficient as a fixed-size data structure (and I also didn’t fix the key and value types) but the execution times here are small enough that this doesn’t matter much. I’ve definitely had premature optimization be lethal to projects before: until there’s a problem with an approach, go with what works!

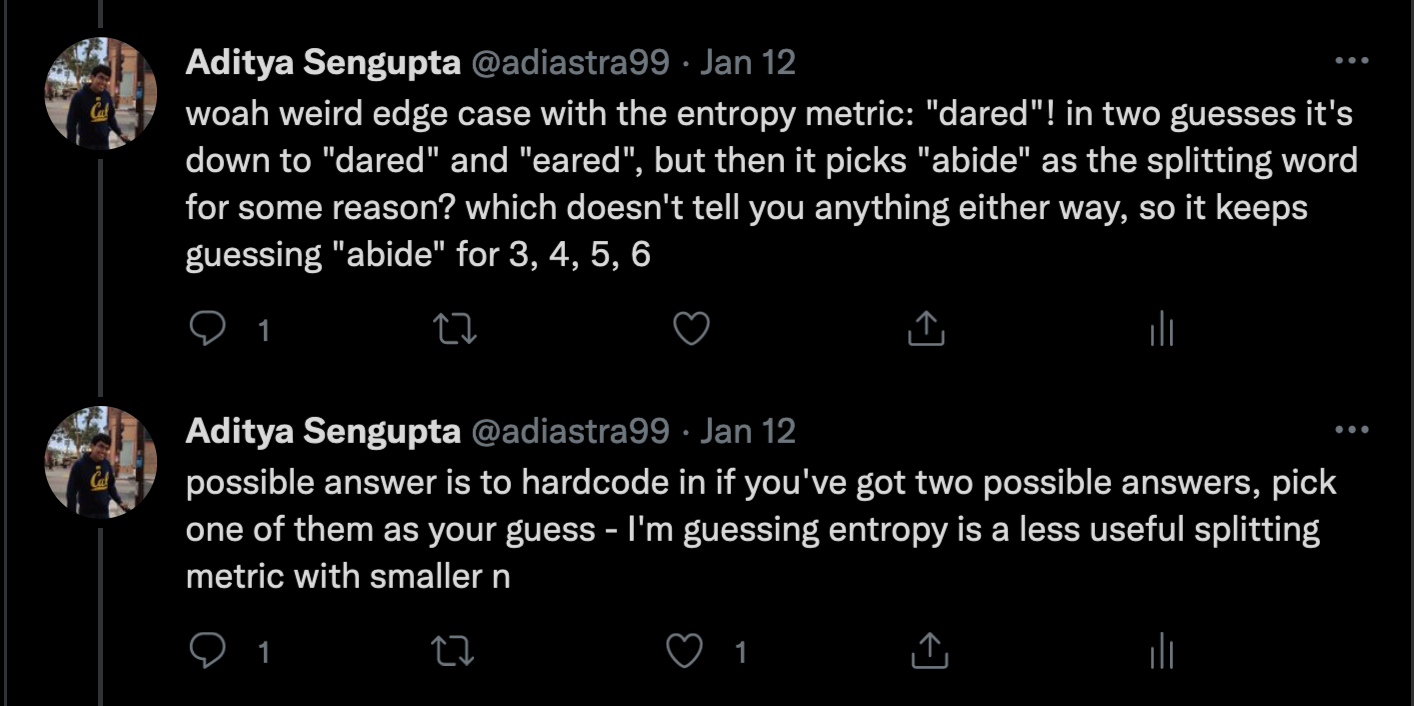

I also have an edge case at the top, which I can most succinctly explain just by reproducing my tweets about it:

This showed up for “dozed” and “oozed” as well! It’s possible my simplifying assumption breaks down when there’s just two words, and the presence of yellow doubles really does matter — all four of these edge-case words have a repeated letter in them. But telling choose to just go with one, then the other, worked perfectly, and with just two words there’s no strategy to split any better than that anyway.

We can get the best starting word, which can be applied to human strategies as well, just by running choose(possibles.answers). On the Wordle corpus, it’s “soare”, and on the Wordmaster corpus, it’s “tares”, both of which back up the generally popular idea that choosing a word with a lot of common letters is a good start.

Does it work?

Shockingly well! This was pretty much my first idea for how a solver should work, and I was surprised by how well it did. It almost always gets the answer within 3 or 4 guesses, even though its paths seem very weird to the human eye. Here’s a few random runs (using an extra function I wrote called play that just loops choose and constrain until there’s a solution):

julia> play("squid")

tares

choil

squid

3

julia> play("zesty")

tares

stopt

zesty

3

julia> play("sharp")

tares

sharn

deked

sharp

4

I particularly like that last one: no human player would see they got “shar” right and go to something completely different. We would keep the rest of the word the same and just guess that last letter. However, the computer sees there’s four different words it could still be: shard, share, shark, sharp. So its question is now: does this word have d, e, k, or p? The entropy split leads it to a word that has three of those four letters, and when it sees no match, it knows only p is left and can say it’s “sharp” with certainty.

It can be a bit unsettling to watch the program go from all grey to all green and know exactly what it’s doing:

There it was trying to figure out if it was brown, crown, drown, or frown.

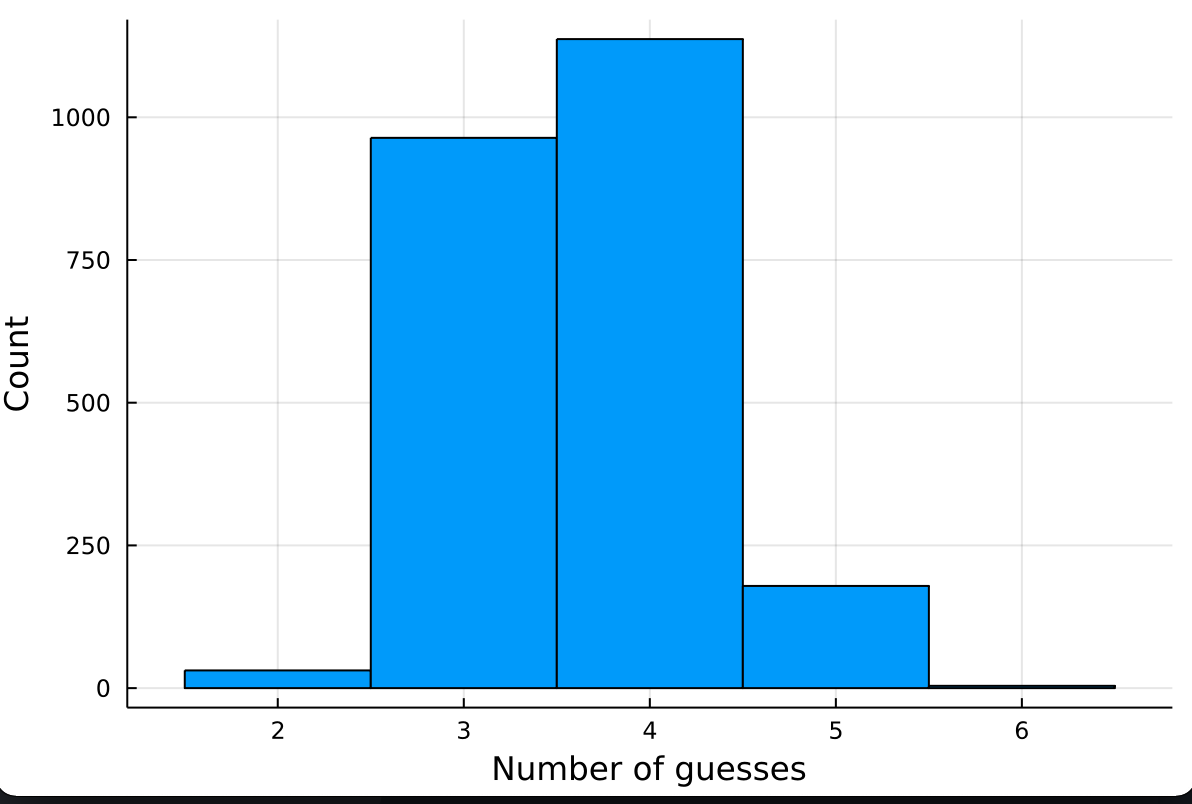

Finally, here’s a histogram of how many guesses it takes to find all the words in the Wordle corpus! The mean is 3.63 and the standard deviation is 0.65.

There’s only four words that take all six guesses: “graze”, “boxer”, “maker”, and “wafer”. It seems that the deadly combination is an uncommon consonant in a common vowel pattern: once you’ve got it down to _A_ER, for example, it’s hard even for the program to figure out what consonants go in those blank slots. There’s 27 possibilities, and it takes a little longer to find enough ways to split up that set of words considering that it starts out so similar.

An interesting thing to note is how few of the splitting words are in the answer set. This makes sense probabilistically: only a fifth of the full set of guesses available are also possible answers, so it makes sense that most of what you guess won’t be in there. I also think the more obscure words that aren’t on the answers list are more likely to have the weird, specific combinations of letters you need in a particular situation to provide the best split.

Summary

One of the coolest things about programming is when you see emergent behaviour that matches what you would intuitively expect, or that you can put human reasoning to. It’s the aspect I like the most about computational science: like any bit of mathematics, it gives you new qualitative insights that even sitting down with a calculator, a log table, and a lot of patience wouldn’t be able to do. I really like this extract from Lockhart’s Lament, a great essay on the problems with K-12 mathematics education:

The reason I enjoyed making this is, well, a little bit for the Twitter clout, but mostly because it turned out to be a fascinatingly intricate problem. I didn’t tell it much about what it was doing, but it managed to talk back and tell me a great deal.